Followup on Hallucination Detection and Recovery (progress report #3.5)

0. Preface

In this followup update to my initial experiment, I report on some additional results as I apply the same approach to more problem instances.

The experiments’ Github repo WakingUp is updated with the improved scripts and new results. In particular, in the repo’s directory episodes I am collecting instances where a model hallucinated, the results of property-based testing that detected the halluciation, and subsequent attempts to fix the error. Once scaled up, we will be able to create a data set of these.

Whereas our earlier projects like Arena, Benchmark and FormalizeWithTest aims to create or collect data sets that are either unlabeled (problems only) or labeled (problems with solutions), here we are creating data of the problem solving process. This can be useful for training / tuning of “reasoning” models. This could be done either via RL, like what Deepseek r1 and (allegedly) o1 & o3 are trained with, or via supervised fine tuning.

What can be learned from such data?

- better world models, of Lean and of the underlying algorithms used. So that next time, the AI won’t hallucinate.

- stronger ability to detect and recover from hallucinations at inference time. One aspect is how best to use the tools that we are providing, e.g. when to invoke what tool, and how to interpret the information the tools return. Another aspect is to perhaps internalize some of the reasoning strategies that our tools help implement; e.g. given the problem and candidate solution, what test input values tend to be critical tests of the correctness of the solution? And once hallucination is detected, what are good strategies to diagnose the source of the error?

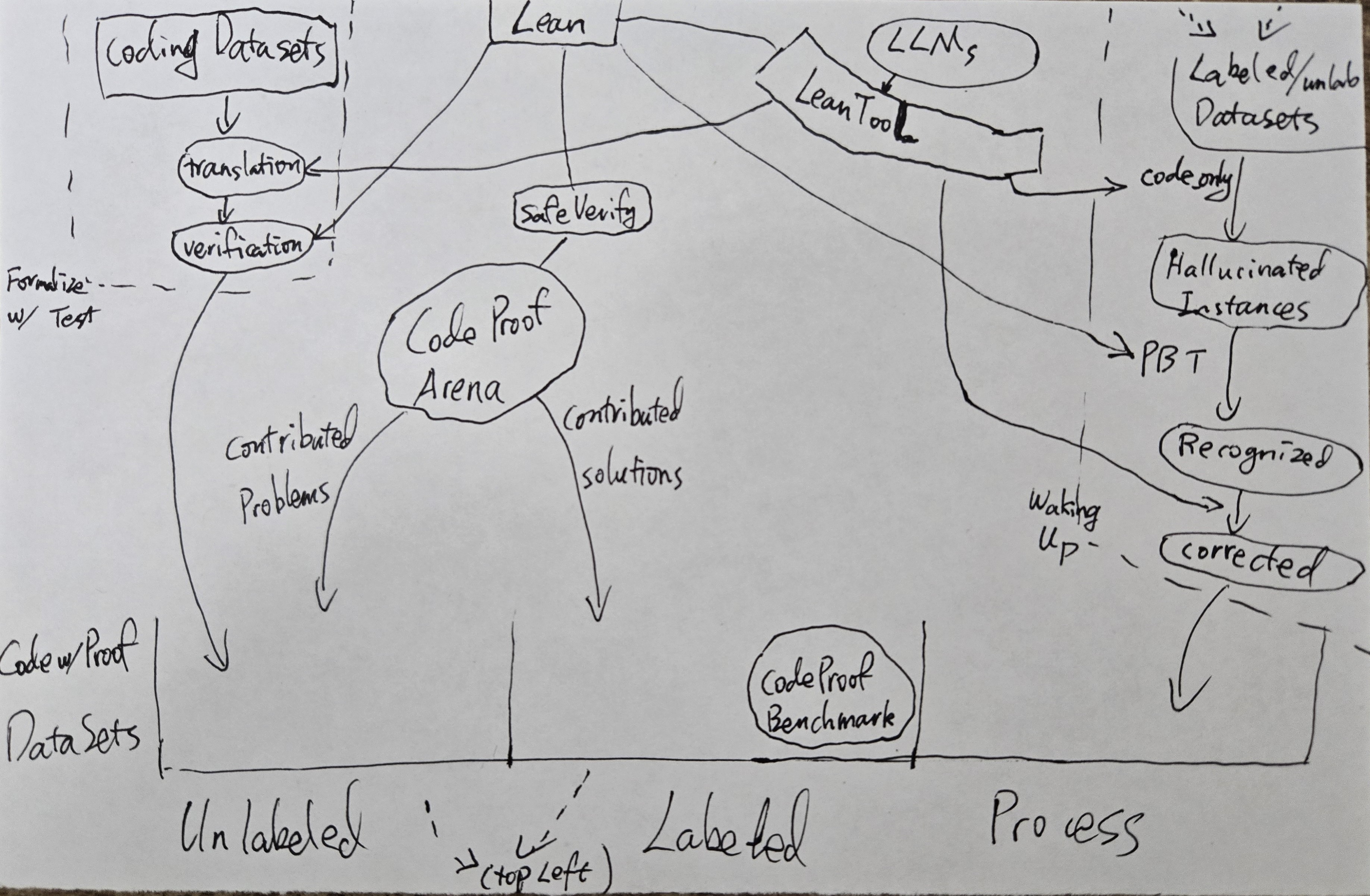

Here is a rough drawing of how our various projects relate to each other in terms of data creation.

1. Creating Beautiful Tables with Sonnet

Another problem from the FormalizeWithTest output was the Beautiful Table problem, description below:

Levko loves tables that consist of n rows and n columns very much. He especially loves beautiful tables. A table is beautiful to Levko if the sum of elements in each row and column of the table equals k.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t know any such table. Your task is to help him to find at least one of them.

Input

The single line contains two integers, n and k (1 ≤ n ≤ 100, 1 ≤ k ≤ 1000).

Output

Print any beautiful table. Levko doesn’t like too big numbers, so all elements of the table mustn’t exceed 1000 in their absolute value.

If there are multiple suitable tables, you are allowed to print any of them.

Examples

Input

2 4

Output

1 3

3 1

Input

4 7

Output

2 1 0 4

4 0 2 1

1 3 3 0

0 3 2 2

Note

In the first sample the sum in the first row is 1 + 3 = 4, in the second row — 3 + 1 = 4, in the first column — 1 + 3 = 4 and in the second column — 3 + 1 = 4. There are other beautiful tables for this sample.

In the second sample the sum of elements in each row and each column equals 7. Besides, there are other tables that meet the statement requirements.

And the function signature to be implemented is:

def beautiful_table (n k : Nat) (h1 : n ≥ 1) (h2 : k ≥ 1) : List (List Int)

The test cases that came with the problem instance are:

{'input': '2 4 (by decide) (by decide)', 'output': '[[1,3],[3,1]]'}

{'input': '4 7 (by decide) (by decide)', 'output': '[[7,0,0,0],[0,7,0,0],[0,0,7,0],[0,0,0,7]]'}

Note that for this problem, given an input there could be multiple correct solutions. The provided test case outputs are not the only solutions; so “failing” them does not necessarily mean that the solution is wrong. A more robust way to establish correctness would be via property-based testing. For now, I will manually judge the correctness of outputs for these two inputs.

Code-only mode

In my original experiment, running code-only mode with the models on this problem returned syntax errors. It turned out the syntax errors were on my part: because the function is returning a complex object with a compound type, I was not parsing the return values in the test cases correctly and that resulted in the errors.

I now fixed it by modifying FormalizeWithTest to output each test case as a dict with separate input and output entries, making it easy to parse.

Running the models in the updated code-only mode, I found that Sonnet 3.5 hallucinates in this problem. (Meanwhile, GPT 4o returned a correct implementation, while Deepseek v3 ran into syntax errors.) Here is Sonnet’s solution:

def make_row (n : Nat) (pos : Nat) (val1 val2 : Int) : List Int :=

List.range n |>.map (fun i => if i == pos then val1 else if i == (n-1) then val2 else 0)

def beautiful_table (n k : Nat) (h1 : n ≥ 1) (h2 : k ≥ 1) : List (List Int) :=

if n == 1 then

[[k]]

else if n == 2 then

[[1, k-1], [k-1, 1]]

else

let baseVal := k / n

List.range n |>.map (fun i =>

if i == n-1 then

make_row n i baseVal (k - baseVal)

else

make_row n i baseVal (k - baseVal))

While one correct approach (which GPT 4o took) was to put k on the diagonal of the matrix and

0 everywhere else, here Sonnet instead tried to put some mass on the diagonal

and the rest off the diagonal.

In this solution it tried to put the off-diagonal mass all on the last column,

which doesn’t work since the column sums will be off.

Recognition

As in our initial experiment, we ran the script pbt.py

on this problem instance and Sonnet’s candidate solution,

which tests Sonnet’s solution using property-based testing.

Some randomly generated input values for n and k would violate the preconditions h1

or h2. These inputs need to be skipped over. (An implementation detail is how to detect that

h1 or h2 are violated from the python side. This is implemented by passing (by decide)

as input arguments for h1 and for h2, and when they are violated, it will result in a compilation error of the generated Lean script.)

Out of 100 (n, k) pairs generated, 32 were skipped due to violating preconditions. For the remaining, 31 returned correct outputs while 37 returned incorrect outputs. An example of input-output pair that failed PBT:

{'inputs': {'n': '4', 'k': '3', 'h1': '(by decide)', 'h2': '(by decide)'},

'output': '[[0, 0, 0, 3], [0, 0, 0, 3], [0, 0, 0, 3], [0, 0, 0, 0]]'}

Correction

Feeding results of PBT back into Sonnet allowed it to fix the error and create a correct implementation. Here is its full reasoning trace, including function calls to the Lean executable (provided by LeanTool) to check for syntax validity as well as checking additional test cases.

Attempt:

Let me analyze the failed test cases and identify the issues with the current solution.

- Looking at the test failures, I notice a pattern. For example, with n=3, k=1:

[[0, 0, 1], [0, 0, 1], [0, 0, 0]]The issue is that:

- The row sums are incorrect: first two rows sum to 1, but last row sums to 0 (should be 1)

- The column sums are incorrect: last column sums to 2 (should be 1)

- The problem is in the current solution’s approach:

- For n>2, it tries to create a pattern where each row has baseVal in position i and (k-baseVal) in the last position

- This creates an unbalanced matrix where:

- The last column gets too many non-zero values

- The last row doesn’t get the right values

- Let’s try a different approach:

- For n=1, keep [[k]]

- For n=2, keep [[1, k-1], [k-1, 1]]

- For n>2, create a cyclic pattern where:

- Each row has exactly two non-zero values that sum to k

- The positions of these values rotate to ensure column sums are also k

Let me implement this idea:

def beautiful_table (n k : Nat) (h1 : n ≥ 1) (h2 : k ≥ 1) : List (List Int) :=

if n == 1 then

[[k]]

else if n == 2 then

[[1, k-1], [k-1, 1]]

else

let baseVal := k / 2 -- Split k roughly in half

List.range n |>.map (fun i =>

let pos1 := i

let pos2 := (i + 1) % n

List.range n |>.map (fun j =>

if j == pos1 then baseVal

else if j == pos2 then k - baseVal

else 0))

{'success': True, 'output': '/var/tmp/tmpur2wqc3d.lean:1:33: warning: unused variable `h1`\nnote: this linter can be disabled with `set_option linter.unusedVariables false`\n/var/tmp/tmpur2wqc3d.lean:1:46: warning: unused variable `h2`\nnote: this linter can be disabled with `set_option linter.unusedVariables false`\n', 'error': None}

Attempt:

Let’s test this solution with some specific test cases that failed before:

#eval beautiful_table 3 1 (by decide) (by decide)

#eval beautiful_table 4 3 (by decide) (by decide)

#eval beautiful_table 3 5 (by decide) (by decide)

{'success': False, 'output': "/var/tmp/tmpkax41b1v.lean:1:6: error: unknown identifier 'beautiful_table'\n/var/tmp/tmpkax41b1v.lean:2:6: error: unknown identifier 'beautiful_table'\n/var/tmp/tmpkax41b1v.lean:3:6: error: unknown identifier 'beautiful_table'\n", 'error': ''}

Attempt:

Let me combine the definition and test cases:

def beautiful_table (n k : Nat) (h1 : n ≥ 1) (h2 : k ≥ 1) : List (List Int) :=

if n == 1 then

[[k]]

else if n == 2 then

[[1, k-1], [k-1, 1]]

else

let baseVal := k / 2 -- Split k roughly in half

List.range n |>.map (fun i =>

let pos1 := i

let pos2 := (i + 1) % n

List.range n |>.map (fun j =>

if j == pos1 then baseVal

else if j == pos2 then k - baseVal

else 0))

#eval beautiful_table 3 1 (by decide) (by decide)

#eval beautiful_table 4 3 (by decide) (by decide)

#eval beautiful_table 3 5 (by decide) (by decide)

{'success': True, 'output': '/var/tmp/tmpe_uscvtc.lean:1:33: warning: unused variable `h1`\nnote: this linter can be disabled with `set_option linter.unusedVariables false`\n/var/tmp/tmpe_uscvtc.lean:1:46: warning: unused variable `h2`\nnote: this linter can be disabled with `set_option linter.unusedVariables false`\n[[0, 1, 0], [0, 0, 1], [1, 0, 0]]\n[[1, 2, 0, 0], [0, 1, 2, 0], [0, 0, 1, 2], [2, 0, 0, 1]]\n[[2, 3, 0], [0, 2, 3], [3, 0, 2]]\n', 'error': None}

(End of Sonnet’s output)

Discussion

This solution is no more and no less correct than GPT 4o’s straightforward solution; but I think it is more creative in some sense, as Sonnet came up with something that I had not thought of.

This reminds me of a comment by Demis Hassabis in his recent interview, in regarding to AlphaGo making the famous move 37 in its match against Lee Sedol, that it is the search on top of the base model that enables the AI to make these creative choices. I think we have a similar situation here, where the inference-time feedback loops we built on top the base model allows the model to iterate through possibilities in the solution space, ending up on something that is both creative and correct.

2. Extending to Code with Proof Benchmark

In our initial experimental set up, we needed a set of problems containing test cases (input-output pairs). What about problem instances without test cases? Well, if we have implementations of correct solutions, we can generate test cases by evaluating the solution on randomly generated inputs.

Our Code with Proof Benchmark is one such dataset: it comes with implementations of solutions in Lean 4 (as well as correctness proofs, which we will not be using directly in this experiment, other than a nice guarantee that these implementations are correct). To be honest, I thought this benchmark might be a bit too easy for this purpose of halluciation detection. The benchmark was designed so that while the coding tasks are often pretty basic, the proof tasks are somewhat more nontrivial. Now we only focus on the coding part. Still, it is a good testing ground since it is available.

I wrote a script that is an adapted version of pbt.py to create the test cases. (The part that generates random input values

is the same; now instead of calling the verification script I just record the output valuese

evaluated by the solutions.)

For some of the problems it was not able to generate test cases

because it could not parse the function signature to extract the types of the input arguments.

An improvement left for future work.

Code-only mode

I tried Sonnet 3.5, Deepseek v3, and GPT 4o as before; I also tried the newly released o3-mini, since it has function calling abilities and therefore can use LeanTool.

We again skip over problem instances where the models did perfectly,

and where the models did not create syntactically valid solutions.

In the end, we identified one problem instance modInv where GPT 4o hallucinated.

The problem description:

write a function that given a natrual number a and a prime number p, returns a natural number x such that (a*x)%p=1. if no solution exists, return none.

Function signature:

def modInv(a: Nat) (p:Nat)(hp:p.Prime): Option Nat

This is indeed one of the few problems in the dataset that can be tricky to implement, as least if you want to solve it using number theory instead of brute force.

GPT 4o’s solution (it tried to do number theory):

import Mathlib

def modInv (a : Nat) (p : Nat) (hp : p.Prime) : Option Nat :=

if Nat.gcd a p = 1 then

let (x, y) := Nat.xgcdAux a p 1 0 0 1

some (x % p)

else

none

This solution failed 1 out of 8 test cases.

Meanwhile, Deepseek and o3-mini failed to output syntactically valid solutions for this problem, while Sonnet did output a correct solution using the brute-force approach:

import Mathlib

def isModInv (a x p : Nat) : Bool :=

(a * x) % p = 1

def modInv(a: Nat) (p: Nat) (hp: p.Prime): Option Nat :=

if Nat.gcd a p = 1 then

let rec findInv (x : Nat) : Option Nat :=

if x ≥ p then none

else if isModInv a x p then some x

else findInv (x + 1)

termination_by p - x

findInv 1

else

none

(While the algorithm is a straightforward loop, doing it correctly in Lean with a valid termination proof can be a bit tricky; so points to Sonnet for being a good Lean coder)

For reference, see my solution from the Benchmark repo. I know very little about number theory, and remember struggling quite a bit on this problem.

Recognition

Here is the formal specification for the problem:

theorem modInv_correct(a:Nat) (p:Nat)(hp:p.Prime):

(∃ x:Nat, (a*x)%p=1)->(a*(modInv a p hp).get!)%p=1

theorem modInv_none(a:Nat) (p:Nat)(hp:p.Prime): (Not (∃ x, (a*x)%p=1))-> modInv a p hp=none

This has a different format than the FormalizeWithTest’s formal specs:

they are straight theorem statements instead of going through property definitions in the FormalizeWithTest case.

As a result the previous pbt.py script cannot be directly applied.

Fortunately, for this problem the first theorem statement can be tested using the built-in Plausible library since the associated property is Decidable; and fortunately this thereom statement was what GPT 4o’s solution failed on. So for now I have a modified PBT script where it tries Plausible if the formal spec is of the CodeProofBenchmark format. Future work is to make this more general and robust.

So for this problem, it created the following Lean script to do property based testing using Plausible:

import Plausible

import Mathlib

@[simp] def modInv (a : Nat) (p : Nat) (hp : p.Prime) : Option Nat :=

if Nat.gcd a p = 1 then

let (x, y) := Nat.xgcdAux a p 1 0 0 1

some (x % p)

else

none

theorem modInv_correct(a:Nat) (p:Nat)(hp:p.Prime):

(∃ x:Nat, (a*x)%p=1)->(a*(modInv a p hp).get!)%p=1 := by

simp

plausible

And the script outputs the following:

/var/tmp/tmpadbqoji3.lean:17:2: error:

===================

Found a counter-example!

a := 13

p := 5

guard: ⋯

x := 7

guard: 1 = 1

issue: 4 = 1 does not hold

(0 shrinks)

-------------------

Different output format, but nevertheless not hard to parse: it failed on

input values a:=13, p:=5.

In other words, we have Recognition.

Debugging and Correction

Feeding the PBT results back to GPT 4o, it was not able to fix the error. Looking at the logs, it was meaningfully engaging with the PBT results (i.e. not blindingly generating new solutions); it acknowledged that the solution failed to output a correct answer for the case a:=13 and p:=5, and investigated possible causes and ways to fix the solution. It also used LeanTool to pass code to Lean to try things out and test assumptions. It just was not able to find a fix, and eventually got stuck.

I think we have found a problem-candidate solution combination that is legitimately hard to correct, even after Recognition.

A wide range of inference-compute techniques can be applied, from different prompts to search-based approaches. I am posting this as an open challenge to interested readers.

I will report what I have tried. One is an additional prompt paragraph with a more detailed breakdown of the process of identifying the source of the error:

You may use the following steps to help identify the error:

- Understand the intention behind the original code. At a high level, what is the algorithm it is trying to impl ement?

- Given the test input, mentally trace execution of the code (without calling Lean) to produce an output. Does i t match the actual output? If no: we have a mismatch of understanding of what the code does. You may use #print command in your code to p rint out the definitions of library functions involved. If yes: go on the next step.

- Given test input, what is the expected output given the abstracted algorithm of the original solution? Does it match the actual output? If no: something wrong happened during the translation from idea to code. If yes: go on the next step.

- Plug the input and actual output to the formal specification (without calling Lean). Do they satisfy the spec? If Yes: we have a mismatch of understanding of what the formal specification means, because the property-based testing result shows that the specification is violated for this input

- Given this input, what would the output need to be in order to satisfy the formal specification?

- If you cannot fix the current approach to produce the correct output, you may try to generate a new solution u sing a different approach.

I think this can be helpful in locating the error, but finding the correct solution might Still be nontrivial.

Another simple thing to try is to do best-of-n: repeat n times whatever task we ask the LLM to do (for this case, to debug and find a correct solution), with increased temperature if possible to have a diverse set of outputs, and then take the best one. (If we adhere to our setting strictly, we do not have access to the test cases here, so we will need to judge the relative performance of solutions via property-based testing. In my implementation of best-of-n I got lazy and used the test cases as judge; for this problem it doesn’t make much difference since we know property-based testing works and I could’ve used PBT with the same results.)

This can potentially be a way to get “unstuck” by generating a diverse set of possible solutions.

I also tried to see if other models can find a fix. (To be clear, they are given GPT 4o’s original solution and the PBT result.) In general, one worry with switching models at this point is that the new model could just generate a solution without needing to look at the original solution, then it is not clear to what extent they are “debugging” / “fixing”.

One answer to this question is that once we have Recognition, all is fair game, including switching models, because Recognition is the signal we need to start some targeted spending of compute. For us, since we know how these models did when trying to solve the problem without access to GPT 4o’s attempt, we can compare.

In the end, o3-mini was able to output a correct solution, in the best-of-3 setting:

import Mathlib

/-- Binary exponentiation modulo m. Computes a^exp mod m. Assumes m > 0. --/

def modPow (a exp m : Nat) : Nat :=

if exp = 0 then 1

else if exp % 2 = 0 then

let half := modPow a (exp / 2) m

(half * half) % m

else (a * modPow a (exp - 1) m) % m

/--

Given a natural number a and a prime number p, returns an option containing x such that (a * x) % p = 1 if it ex

ists, and none otherwise.

In a prime field ℤ/pℤ, a has an inverse if and only if a mod p ≠ 0. In that case, by Fermat’s little theorem, th

e inverse is a^(p-2) mod p.

--/

def modInv (a : Nat) (p : Nat) (hp : p.Prime) : Option Nat :=

if a % p = 0 then

none

else

some (modPow a (p - 2) p)

In o3-mini’s original attempt on this problem without seeing GPT 4o’s solution, it tried to implement its own version of extended GCD, but ran into syntax issues. Perhaps seeing another failed attempt at using extended GCD to solve the problem made it decide to switch to a different approach.

Gemini (version gemini-2.0-flash-exp) also made a correct solution, in the setting with the more extensive debugging prompt given above.

This one followed GPT 4o’s origional approach but fixed the errors in the usage of the library functions,

and made the syntactically correct casting between Nats and Ints.

import Mathlib

open Nat

def modInv (a : Nat) (p : Nat) (hp : p.Prime) : Option Nat :=

if Nat.gcd a p = 1 then

let (x, y) := xgcd a p

let x := x % Int.ofNat p

if x < 0 then

some (Int.toNat (x + Int.ofNat p))

else

some (Int.toNat x)

else

none

Try your favorite model / system prompt / inference-time-compute strategy on these, and let me know how they did!