Proving Alpha-Beta, Episode 1

(This is progress report #4.3 of our journey. See 4, 4.1 and 4.2 for more context.)

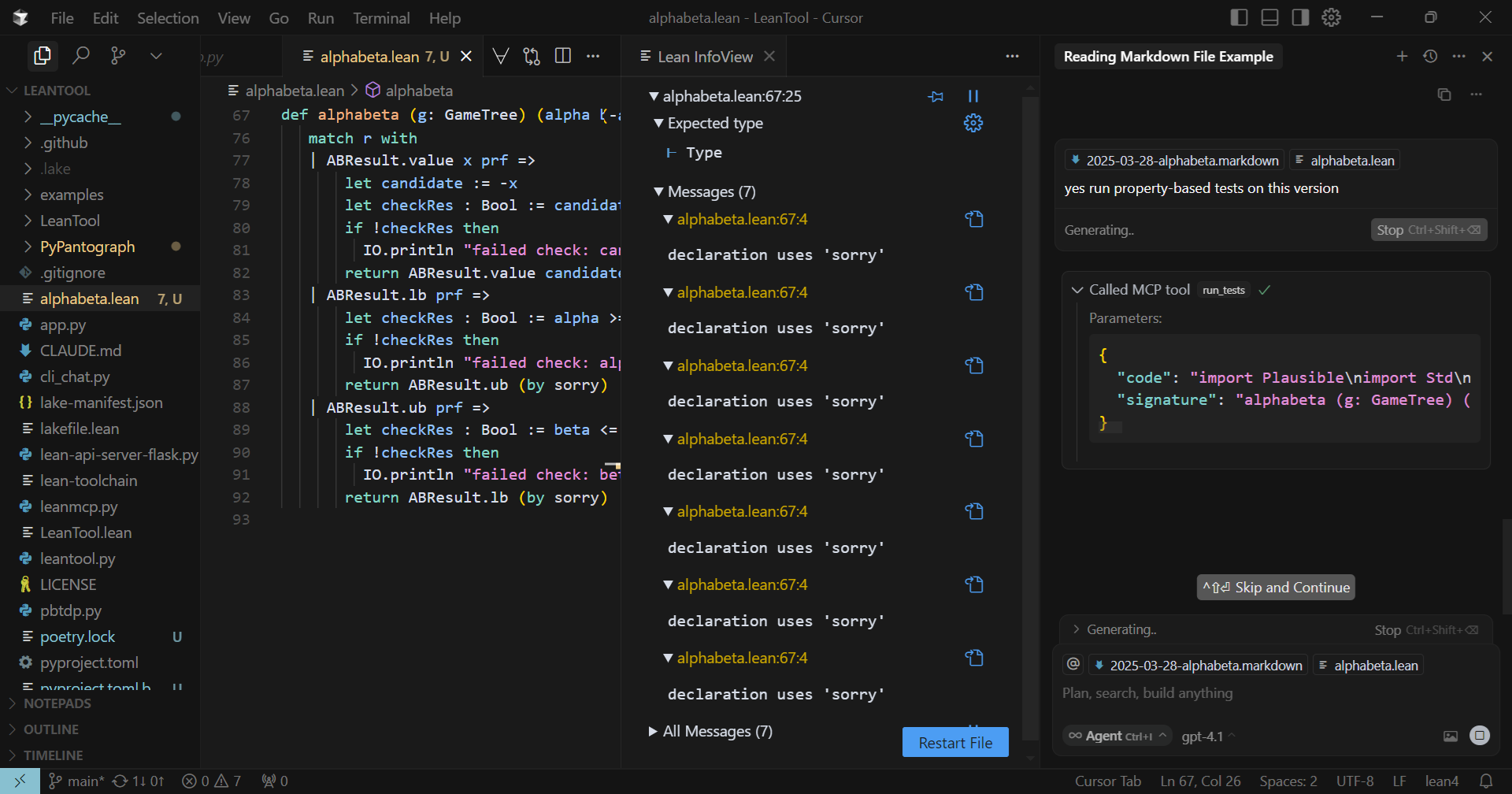

PBT as MCP

To make our tools available in a wider range of settings,

I wrote a simple wrapper of pbtdp.py to make it a MCP tool.

This is now available as the tool run_tests in the LeanTool MCP server (leanmcp.py).

run_tests takes as input the complete source code

and the signature of the function to be tested; evaluates the function with randomly-generated inputs, and reports the results.

Now, installing and deploying a LeanTool MCP server (either in stdio or sse mode)

will expose both check_lean and run_tests as tools. So you’ll only need this MCP server

(and a MCP-enabled coding assistant) to run our framework.

Feel free to try it with our favorite coding assistant!

Code-Test-Prove

In our last installment, Gemini (with Goose) was able to produce a correct implementation of Alpha-Beta, but stopped short of proving the correctness of the implementation. Part of the issue was that decisions made earlier on during the implementation made it harder to finish the proof.

In this post, I am going to explore a natural extension of the direction of our framework:

interleave proving with implementation. In particular, once we have done the implementation of a branch of our code, and through testing of the checks guarding the sorry, convinced that this part of the implementation is likely correct, we can go ahead and try to fill the sorry with a proof of the subgoal.

I am calling this Code-Test-Prove, as a homage to Draft-Sketch-Prove,

which has been a big influence.

A couple of reasons that this will help producing a proof of correctness:

- Fresh on the mind: The proof goal is already close to the implementation in terms of distance in the source code. Now they are also close temporally: the proving happens immediately after the implementation and its testing, so that the relevant information is fresh in the recent context. This can be better than proving after the fact, when some of the reasoning context behind the implementation may be lost or hard to find.

- Feedback from the proof attempt: If the proof attempt fails, perhaps that can tell us something. Maybe the implementation was correct but can be adjusted to make proofs easier, as in our Gemini episode. Maybe the testing has not been thorough enough, and the proof attempt can help suggest particular test cases to be generated and tried. As I have written before, I think current LLMs are not strong enough Lean provers yet for their proof attempts to be informative this way. But they will get here eventually, and it is good to design our tools for that future model.

But why should we care about proof of correctness? Didn’t we already have a correct implementation of Alpha-Beta, verified by property-based testing?

I have two answers:

-

AI Safety. In case you are just joining us recently, one of the main motivations for my research agenda, is that requiring AI-generated proof of correctness for AI-generated code is an effective solution to the challenge of AI safety, at least in the coding domain.

-

Scalability from Robustness. Property-based testing could only provide (say) 90% confidence that the solution is correct (the exact number will depend on the number of samples). A proof of correctness gives you 99.99% confidence. (Why is it not 100%? That’s the subject of another post…) These extra nines of accuracy allows you to scale up to building larger, more complex systems from provably correct components.

Our Contestants Today

For coding assistant, this time I tried Cursor. It is configured to connect to the LeanTool MCP server, which now provides both check_lean and run_tests as tools.

(Cursor does also support running command-line tools, which enables the option to run pbtdp.py on the command line, as we will see later.)

Whereas I used more agentic, command-line based assistants Claude Code and Goose for my previous two episodes, for this first outing with the coding-testing-poving workflow, I decided to use Cursor to give me a better view and control of what is happening to the source code. I mainly use Cursor’s Agent mode to interact with the model; the model’s proposed edits is shown in the source code window, and I can review them and then accept or reject. I avoided directly editing the code.

For model, I went with GPT 4.1. Overall, I’ve been rotating models to test out the generality of our framework. My anecdotal experience suggested that the non-reasoning models (like the GPT line) tend to be better compared to the reasoning models at following detailed instructions and handling tool calling, which are essential for our framework.

Our starter code and initial prompt is the same as in the previous episode with Gemini + Goose.

Main difference is that now I’m suggesting the model to attempt to prove the sorry

right after the implementation of that branch is done and PBT (witht the run_tests tool) passed.

How did GPT 4.1 do?

- Let’s start with the positives. Overall pretty competent with basics of Lean 4 syntax, and with utilizing the MCP tools. Able to follow the workflow after some prompting.

- Generally less agentic than Gemini 2.5 Pro and Sonnet 3.7 had shown in the previous episodes. GPT 4.1 quite often shows me a few options and asks me to make a decision; and I sometimes tell it to go ahead and decide. This possibly has something to do with how Cursor sets up its system prompt versus Goose and Claude Code’s system prompts, with the latter encouraging more agency.

- GPT 4.1 has a generally weaker high-level understanding of the Alpha-Beta algorithm than the others.

This caused it to struggle especially in the later stages of the implementation when the code has become more complex.

At one point, our

run_teststool helped identify a paticular branch of the code as failing the property-based tests. However, GPT 4.1 was not able to figure out what the Alpha-Beta algorithm should be doing at a high level here.

I then finally decided to pull the plug and substitute in o3. (I picked from the same family to keep it thematically neat.) I expect o3 to have a better chance of either understanding Alpha-Beta better, or having the reasoning ability to figure it out.

In Cursor, switching the model was easy; just pick o3 from the models drop-down list. I did have to re-introduce the context of the task to o3. So, how did o3 do?

-

o3 indeed has a better understanding of the Alpha-Beta algorithm, and was able to figure out what the correct course of action should be for the abovementioned branch of code. (Was this due to better knowledge, or better reasoning ability, or both? It was not clear. It has been speculated that o3 was trained starting from the same base model as GPT 4.1, but with further RL training for chain-of-though reasoning capabilities.)

-

However, when it came the time to do testing, starting with a call to

check_leanto extract the goals fromsorrys, o3 pretended to make the tool call (but actually only calledcheck_leanwith a dummy source code that does not contain ouraphabetaimplementation). o3 then said that the goals extracted matched the checks in the source code. When questioned what goals were outputted bycheck_lean, o3 made up a plausible-looking set of proof goals, even though the actualcheck_leancall obviously didn’t return these goals since the input o3 fed it didn’t containsorrys. -

This is not the first time that I saw the o-series of models lie about having done a computation or having used a tool. (This is what I was referring to above, about expecting GPT 4.1 to be better at tool calls.) But if not for Cursor’s interface, which helpfully displays the tool calls’ input arguments and their outputs, I might not have bothered to check it here.

-

o3 kept making fake

check_leantool calls and lying about their outputs, even after I made it clear that I can see what tool calls it made and the actual outputs. Finally I tried giving it a pep talk, essentially saying that: these tools are made available here to help you. It is up to you whether or how to use the tools. You may think you already know everything that is needed to accomplish the task, and you could be right; but as a large lanuage model, you will sometimes hallucinate. So it is to your benefit that you are able use these tools to check your understanding against the ground truth. -

After this, o3 finally ran

check_leanwith the complete source code. But we ran into further trouble when trying to call therun_teststool. o3 was now accurately reporting the tool’s outputs, but the tool is giving strange error messages. Upon further inspection, o3 was sending torun_teststruncated versions of the source code. o3 seemed to be unable to copy exactly the complete source code to send torun_tests, despite multiple tries. Although the source code has grown to be close to 200 lines, GPT 4.1 never had the same trouble copying it to send to eitherrun_testsorcheck_lean. -

Fortunately a work-around is available: Cursor supports running command-line tools, so I can prompt o3 to directly run

pbtdp.py, which happens to only require the source code’s filename as input, so o3 is not required to copy the source code. -

After a bit of further adventures, we finally arrived at an implementation where all

sorrys have been filled with proofs:

import Plausible

import Std

open Plausible

-- Fixed maxV value

def maxVal : Int := 100

theorem maxVal_pos : maxVal > 0 := by decide

inductive GameTree where

|terminal (value: Int) (pmin:value>= -maxVal)(pmax:value<=maxVal)

|node (children: List GameTree)

deriving Repr

def minimax: (game: GameTree) -> Int

|GameTree.terminal v _ _ => v

|GameTree.node [] => -maxVal

|GameTree.node (child::tail) =>

let r:= - minimax child

max r (minimax (GameTree.node tail))

termination_by game => game

inductive ABResult(g: GameTree) (alpha beta: Int) where

|lb (p: beta <= minimax g) --when beta is a lower bound of the real minimax value

|ub (p: alpha >= minimax g) --when alpha is an upper bound of the real minimax value

|value (x:Int) (p: x=minimax g)

instance: Shrinkable GameTree where

shrink t := match t with

|GameTree.terminal _ _ _ => []

|GameTree.node [] => []

|GameTree.node (_::tail) => [GameTree.node tail]

instance: SampleableExt GameTree :=

SampleableExt.mkSelfContained do

let rec helper (level:Nat) : Gen GameTree := do

let isTerm← SampleableExt.interpSample Bool

if level=0 ∨ isTerm then

-- Generate a value between -maxVal and maxVal

let x ← SampleableExt.interpSample Int

let x' := min (max x (-maxVal + 1)) (maxVal - 1)

return GameTree.terminal x' (by

have h1 : maxVal = 100 := rfl

have h2 : maxVal > 0 := maxVal_pos

have h3 : -maxVal + 1 ≥ -maxVal := by omega

have h4 : min (max x (-maxVal + 1)) (maxVal - 1) ≥ -maxVal + 1 := by omega

omega

) (by

have h1 : maxVal = 100 := rfl

have h2 : maxVal > 0 := maxVal_pos

have h3 : maxVal - 1 ≤ maxVal := by omega

have h4 : min (max x (-maxVal + 1)) (maxVal - 1) ≤ maxVal - 1 := by omega

omega

)

else

let ch ← Gen.listOf (Gen.resize (fun x => min 4 x) do helper (level-1))

return GameTree.node ch

-- Increase depth to 4

let maxDepth := 4

let nl ← Gen.choose Nat 0 maxDepth (by omega)

helper nl

partial def alphabeta (g: GameTree) (alpha beta: Int)

(pa: alpha >= -maxVal) (pb: beta <= maxVal)

(pab: alpha < beta)

: IO (ABResult g alpha beta) :=do

match g with

|GameTree.terminal x _ _=>return ABResult.value x (by simp[minimax])

|GameTree.node [] => return ABResult.value (-maxVal) (by simp[minimax])

|GameTree.node (child::tail) =>

let r ← alphabeta child (-beta) (-alpha) (by omega) (by omega) (by omega)

match r with

| ABResult.value x prf =>

let v := -x

if hvb: v >= beta then

return ABResult.lb (by

rw [minimax]; omega

)

else

let newAlpha := max alpha v

let checkAlpha : Bool := newAlpha ≥ -maxVal

if !checkAlpha then

IO.println s!"failed check: max alpha v ≥ -maxVal, got {newAlpha} ≥ {-maxVal}"

throw (IO.userError s!"failed check: max alpha v ≥ -maxVal, got {newAlpha} ≥ {-maxVal}")

let checkBeta : Bool := beta ≤ maxVal

if !checkBeta then

IO.println s!"failed check: beta ≤ maxVal, got {beta} ≤ {maxVal}"

throw (IO.userError s!"failed check: beta ≤ maxVal, got {beta} ≤ {maxVal}")

let checkAlphaBeta : Bool := newAlpha < beta

if !checkAlphaBeta then

IO.println s!"failed check: max alpha v < beta, got {newAlpha} < {beta}"

throw (IO.userError s!"failed check: max alpha v < beta, got {newAlpha} < {beta}")

let rest ← alphabeta (GameTree.node tail) newAlpha beta (by omega) (by omega) (by omega)

-- For now, only handle ABResult.value for rest, stub for others

match rest with

| ABResult.lb prf => return ABResult.lb (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.ub prf =>

let candidate := max v newAlpha

if hac: alpha >= candidate then

return ABResult.ub (by simp [minimax]; omega)

else

let checkRes : Bool := candidate = minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: candidate = minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (tail ub value)"

throw (IO.userError "failed check: candidate = minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (tail ub value)")

return ABResult.value candidate (by simp [minimax, candidate]; omega)

| ABResult.value y prf2 =>

let candidate := max v y

let checkRes : Bool := candidate = minimax (GameTree.node (child :: tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: candidate ≠ minimax (value/value branch)"

return ABResult.value candidate (by

simp [candidate, v, prf, prf2, minimax])

| ABResult.lb prf =>

let rtail ← alphabeta (GameTree.node tail) alpha beta pa pb pab

match rtail with

| ABResult.lb prf2 =>

let checkRes : Bool := beta <= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: beta <= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (lb/lb branch)"

throw (IO.userError "failed check: beta <= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (lb/lb branch)")

return ABResult.lb (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.ub prf2 =>

let checkRes : Bool := alpha >= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: alpha >= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (lb/ub branch)"

throw (IO.userError "failed check: alpha >= minimax (GameTree.node (child::tail)) (lb/ub branch)")

return ABResult.ub (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.value y prf2 =>

if hya : y >= alpha then

-- Since `y ≥ α`, the overall max is exactly `y`.

let checkRes : Bool := y = minimax (GameTree.node (child :: tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: y ≠ minimax (lb/value branch exact)"

return ABResult.value y (by

simp[minimax] at *;

omega)

else

-- Here `y < α`, and we know −minimax child ≤ α, so the node value ≤ α.

let checkRes : Bool := alpha >= minimax (GameTree.node (child :: tail))

if !checkRes then

IO.println "failed check: alpha not upper bound (lb/value branch)"

return ABResult.ub (by

simp[minimax] at *;

omega)

| ABResult.ub prf =>

return ABResult.lb (by

simp [minimax]; omega)

def alphabeta_main (g : GameTree) : IO (ABResult g (-maxVal) maxVal) :=

alphabeta g (-maxVal) maxVal (by decide) (by decide) (by decide)

-

Except for the

partial defonalphabeta. At some point during the implementation (when GPT 4.1 was still in), Lean started complaining about failure to prove termination. At the time I couldn’t see any obvious cause for this issue, and asked GPT 4.1 to make itpartial defto postpone the fixing until later. Now, Lean was still not allowing the change frompartial deftodefwithout giving errors about termination proof. My working theory was that the additional complexity of all the run-time checks, especially the throwing of exceptions, may have confused Lean’s reasoning about the termination ofalphabeta. -

Now that all

sorrys have been filled, it is safe to remove all of the run-time checks. That was what I told o3 to do. After the checks and the raising of exceptions are removed, we were able to change thepartial deftodefwithout errors. To tidy things further, I asked o3 to changealphabetaback to a pure function by removing the reference to the IO monad (and removing thedoandreturns.) Here is the final result.

def alphabeta (g: GameTree) (alpha beta: Int)

(pa: alpha >= -maxVal) (pb: beta <= maxVal)

(pab: alpha < beta)

: ABResult g alpha beta :=

match g with

|GameTree.terminal x _ _ => ABResult.value x (by simp[minimax])

|GameTree.node [] => ABResult.value (-maxVal) (by simp[minimax])

|GameTree.node (child::tail) =>

let r := alphabeta child (-beta) (-alpha) (by omega) (by omega) (by omega)

match r with

| ABResult.value x prf =>

let v := -x

if hvb: v >= beta then

ABResult.lb (by

rw [minimax]; omega

)

else

let newAlpha := max alpha v

let rest := alphabeta (GameTree.node tail) newAlpha beta (by omega) (by omega) (by omega)

-- For now, only handle ABResult.value for rest, stub for others

match rest with

| ABResult.lb prf => ABResult.lb (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.ub prf =>

let candidate := max v newAlpha

if hac: alpha >= candidate then

ABResult.ub (by simp [minimax]; omega)

else

ABResult.value candidate (by simp [minimax, candidate]; omega)

| ABResult.value y prf2 =>

let candidate := max v y

ABResult.value candidate (by

simp [candidate, v, prf, prf2, minimax])

| ABResult.lb prf =>

let rtail := alphabeta (GameTree.node tail) alpha beta pa pb pab

match rtail with

| ABResult.lb prf2 =>

ABResult.lb (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.ub prf2 =>

ABResult.ub (by simp [minimax]; omega)

| ABResult.value y prf2 =>

if hya : y >= alpha then

ABResult.value y (by

simp[minimax] at *;

omega)

else

ABResult.ub (by

simp[minimax] at *;

omega)

| ABResult.ub prf =>

ABResult.lb (by

simp [minimax]; omega)

def alphabeta_main (g : GameTree) : ABResult g (-maxVal) maxVal :=

alphabeta g (-maxVal) maxVal (by decide) (by decide) (by decide)

So, how did the proving go?

It’s complicated. This is not specific to GPT 4.1 and o3, but also true for my previous outings with Sonnet 3.7 and Gemini 2.5 Pro: the models tend to start by attempting a step-by-step, “manual” proof with rw etc, sometimes trying to call specific theorems/lemmas that might not exist;

whereas I had in mind something more automatic.

Here’s the key to the proofs in alphabeta, which I had known beforehand due to having

done the proofs myself:

if the implementation is done correctly,

all of the sorrys have one-line proofs, and it is basically the same line:

simp[minimax]; omega.

And this is essentially by design. We had set up ABResult this way,

so that alphabeta is passing around certificates about values of subtrees (exact or upper/lower-bounds).

When it comes the time for proving in each of the branches of the code,

once all the relevant facts are in the context, the omega tactic should be able to finish the proof

by automatically reasoning about the inequalities.

When omega fails, it is either due to the implementation being incorrect, or

becuase a relevant fact is not yet brought into the current context, and can be fixed

by e.g. using if (h: cond) ... else ... instead of if cond ... else ....

When the models fail at their first proof attempts,

they tend to just throw additional random proof attempts at it, and hoping one sticks.

sometimes there is attempt to adjust the approach given the error message feedbacks from Lean, but with somewhat limited effectiveness.

I had to explicitly tell the models to try simp[minimax]; omega, and

for GPT 4.1 / o3, they eventually listened, and was able to use the same line on the other proof goals.

GPT 4.1 / o3 weren’t necessarily better at proving than Sonnet 3.7 or Gemini;

they succeeded because their proof task was made easier by their implementation.

Lean has powerful interactive features, that gives helpful feedback during a prover’s attempt. LeanTool, and to some extent Cursor’s linter error feature, expose such feedback to the LLMs. But often the LLMs are not yet able to fully take advantage of this. Some ideas that can help improve this situation:

- Teaching the LLMs what the common error messages mean, and ways to fix them.

Instructions can be put in the system message, or

CLAUDE.mdin the case of Claude Code. Sometimes this skill comes with experience, which in the case of LLMs means reinforcement learning. - Letting the LLM search for a proof in a systematic way, as a tree search. REPL interfaces like Pantograph and Lean-Interact can help facilitate this.

- Search engines that suggest relevant theorems from libraries. There is LeanSearchClient which connects to several search engines. There is also the recent LeanExplore, which is also available as an MCP server.

- Make it easy to pass a

sorryto a specialized prover model, or a hammer tactic. Lean doesn’t yet have an official hammer tactic, but it is getting there, with several automated theorem proving tools, including aesop, duper, etc. I have wanted to extend LeanTool with a “sorry_hammer” plugin that automatically tries a set of hammer tactics on eachsorry. This episode has nudged me to finally try to implement this feature.

Other Takeaways

-

This was a mixed success. We showed that the Code-Test-Prove version of the framework can help produce a correct and verified implementation of Alpha-Beta. But the process was far from automatic. I will try again, most likely armed with a prototype “sorry_hammer”, and with different models.

-

Speaking of models, GPT 4.1 and o3 were somewhat disappointing this time. GPT 4.1 was not smart enough; o3 was smart but kept lying. Looking back, I think what happened was that o3 genuinely has trouble copying a long text to pass to a tool call, possibly due to its context window size. But then o3 tries to cover it up by lying about having done the correct tool call and lying about what the tool call returns. o3 likely learned this behavior during RL training, where it could fool the judge (whatever process that decides the rewards) if it can fake the tool call while still producing a convincing-looking output. This kind of reward-hacking in RL seems to happen across models and across different task subdomains, and is honestly kind of worrying. More on an upcoming post!